When Will China Use Force to Reunite with Taiwan? Hu Xijin Explains His Position

How Security Fears Shape Public Views of the US-China Trade War

- Analysis

- David Bulman

- 19/10/2022

- 0

This analysis draws from David Bulman’s recent article, ‘Instinctive Commercial Peace Theorists? Interpreting American Views of the US–China Trade War,’ in the peer-reviewed journal Business & Politics, accessible here.

Bulman is the McGovern-Muller Assistant Professor of China Studies and International Affairs at Johns Hopkins SAIS. His personal website can be found here.

For four years, the United States and China have fought a trade war and subjected approximately half of each other’s imports to escalated tariffs. The Trump administration initiated this trade war in 2018 with a clear political logic: Americans supported the trade war for economic reasons—increasingly attributing the loss of manufacturing jobs and wage stagnation to trade integration with China—as well as more psychological reasons, including preferences to avoid trading with an “undesirable” partner and suspicions of being taken advantage of by China’s unfair trade policies. Public opinion surveys from 2018 suggested that unfavorable views of China, perceptions of non-reciprocal trade, and partisanship (namely Trump support) drove high levels of support for the trade war.

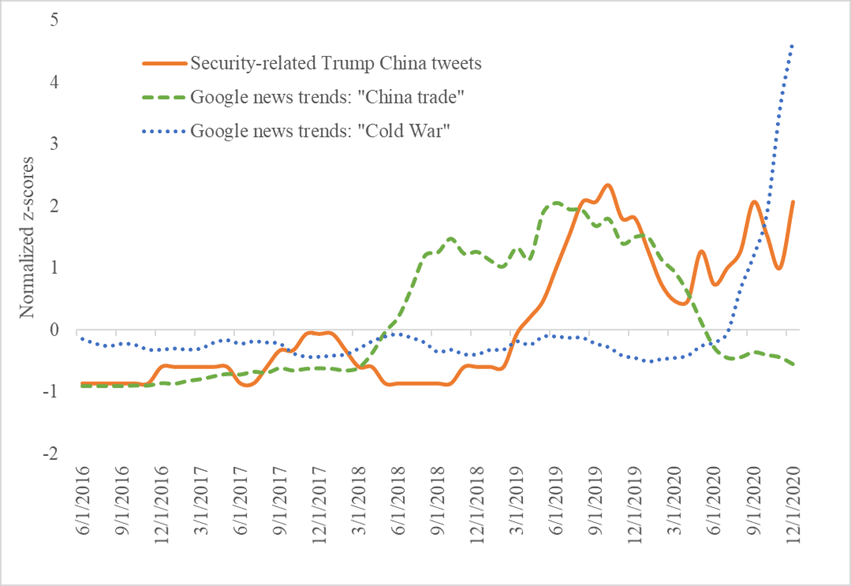

Yet American views of the trade war may have shifted over the past four years, particularly as the US-China bilateral relationship has become increasingly antagonistic and securitized. Americans have never been so sour on China: 79 percent of Americans perceived China “unfavorably” in 2021, up from 45 percent when the trade war began in early 2018. A “master narrative” of China as a security threat and revisionist power dominated US media beginning in 2018 and crowded out narratives emphasizing cooperation. Tellingly, Trump’s tweets on China shifted from trade topics towards security topics in early 2019 (as seen in the solid orange line in Figure 1 below), and these remained elevated through 2020. Public interest in trade with China trade, as proxied by Google News search trends (represented by the green dashed line below), surged with the trade war’s initiation but then faded in 2019 as security-related Trump China tweets rose. These China “trade” searches were replaced by a surge in Google News searches for “Cold War” in 2020 (blue dotted line). This growing security-focused great power competition narrative coincided with increasing fears of China as a direct military threat: in 2021, 45 percent of Americans considered China to be America’s “greatest enemy”, up from 11 percent in 2018, and 71 percent of Americans were worried about the possibility of war with China.

Note: Security-related China tweets include all Trump tweets that reference China in addition to one of the following terms: enemy, military, security, threat, defense, South China Sea, Taiwan, or communism. Both Google News trends are calculated as six-month rolling averages. All three series are converted into normalized z-scores to facilitate trend comparison. All copyrights are reserved to the author. For more details, please see the bottom of the page.

It may seem intuitive that in the face of growing antagonism and security fears, Americans would become increasingly wary of economic integration with China and supportive of the trade war. This seems to be the view of the Biden administration, which has kept the Trump tariffs in place. This view also finds support in international relations theory: according to a realist theory of “security externalities”, individuals may oppose trade with potential adversaries because these adversaries could use the trade proceeds to boost their militaries. Yet IR theory also suggests an alternative liberal response consistent with “commercial peace” theory: individuals may support economic integration with adversaries as a way of reducing the likelihood of conflict. In other words, as Americans become increasingly concerned that the US and China have entered into a new cold war, they may support trade integration to prevent this war from becoming hot. Indeed, during the original Cold War, the American public consistently supported increased trade with the Soviet Union, with support often increasing along with threat perceptions.

In a recent article, I presented findings from original public opinion surveys that explored how security concerns shape American preferences regarding the trade war, attempting to adjudicate between these two IR theories: do fears of conflict increase protectionist sentiment, consistent with “securities externalities” theory, or do they increase support for tariff removal, consistent with “commercial peace” theory? Over 2000 respondents participated in these surveys exploring the reasons for American support for the trade war and whether Americans with deeper security concerns have become more or less supportive of the trade war over time.

Who supports the trade war, and how has this changed?

The surveys first asked respondents whether they initially supported the trade war, expecting that existing trade preference theories related to expected economic gains, reciprocity concerns, xenophobia/unfavorability, and partisanship should explain initial support. Specifically, I expected that initial support for the trade war should be greater among non-college-educated Trump voters who are highly nationalistic, have unfavorable views of China, and believe that China engages in unfair trade practices. The surveys then asked respondents whether they were more or less supportive of the tariffs today as well as whether respondents perceived the US and China as engaged in a new cold war, a proxy for heightened security concerns. I expected that, although existing trade preference theories should help explain initial trade war support, security concerns should have more explanatory power when it comes to shifting trade war support. Specifically, rising security concerns should correlate with declining trade war support, consistent with commercial peace theory.

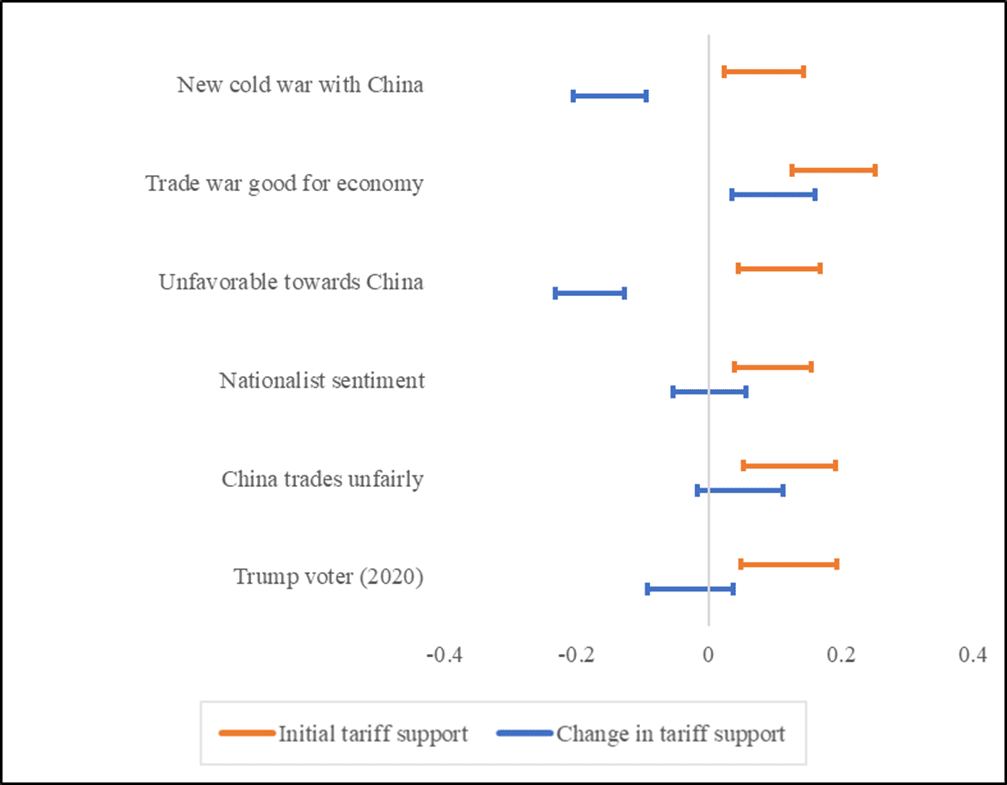

Figure 2 shows how various individual-level characteristics and beliefs help to explain initial support for the tariffs (orange bars) and reported changing levels of trade war support (blue bars). For those more familiar with political science research methods, these are based on confidence intervals for marginal effects from regression analysis. Looking first at the orange bars representing correlates of initial support, I found high support among those who think the trade war is good for the economy (economic self-interest); those with unfavorable views of China and high degrees of nationalism (xenophobia); those who believe China engages in unfair trade (reciprocity); and Trump voters (partisanship). But, as expected, these characteristics have less explanatory power when it comes to change in support for the trade war (blue bars). In contrast, identification of a new cold war with China, while positively associated with initial trade war support, has a strong negative correlation with change in trade war support. Additionally, individuals with unfavorable views of China have also become less supportive of the tariffs, possibly because individuals that look on China unfavorably also perceive a higher threat potential. The effects are large: all else equal, identification of a new cold war leads to 15 percent less support for the tariffs today, while unfavorable views of China lead to 18 percent less support.

Note: All bars correspond to 95 percent confidence intervals for marginal effects from logit models. Orange bars correspond to self-reported initial support for the 2018 tariffs. Blue bars correspond to self-reported change in support for the 2018 tariffs today. Please see original text for technical details. All copyrights are reserved to the author. For more details, please see the bottom of the page.

Who believes in the commercial peace?

Is it reasonable to interpret the association between security concerns and declining tariff support as indicative of instinctive support for commercial peace theory? The surveys gauged respondents’ explicit support for commercial peace theory by asking them the degree to which they believed that bilateral trade lowered the risk of war with China. Ostensibly, individuals with this view should have been less supportive of the tariffs to begin with, and, as security concerns grew, they should have become increasingly opposed to the tariffs. Regression analysis supports this: explicit agreement with commercial peace theory was correlated with 19 percent less support for the tariffs initially and a 16 percent decline in support from 2018-2021.

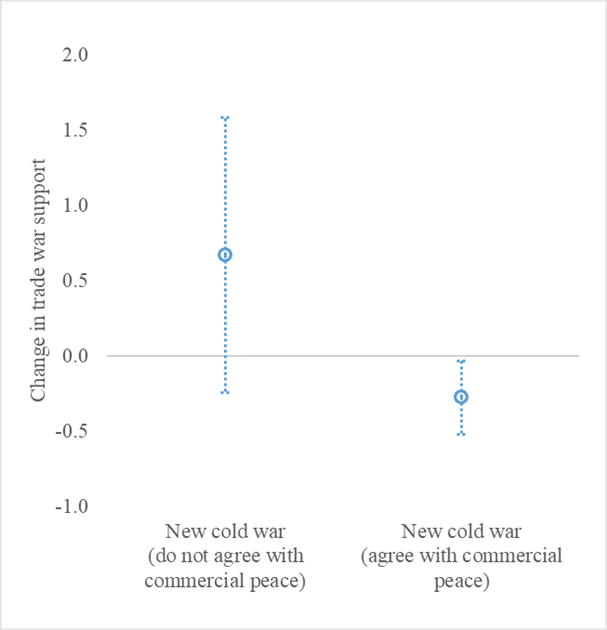

Additionally, this effect should be enhanced by elevated security concerns: individuals worried about conflict should give more weight to trade’s expected security effects, while individuals who believe in the commercial peace but perceive a low risk of conflict should have unaltered trade preferences. To test this, I repeated the above analysis including all of the same covariates as well as an interaction effect between commercial peace support and identification of a new cold war. Figure 3 below shows the results graphically. The point on the left shows that identification of a new cold war predicts increasing trade war support when respondents do not believe in the commercial peace. In contrast, as seen in the point on the right, identification of a new cold war predicts decreasing trade war support when respondents believe in the commercial peace. In other words, as expected, increasing opposition to the trade war is driven by heightened security concerns in addition to an instinctive commercial peace support; independently, these characteristics have no effect.

Note: Bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals for marginal effects from logit models, with interaction terms between cold war identification and commercial peace belief. All copyrights are reserved to the author. For more details, please see the bottom of the page.

As an additional test to see whether the above interpretation is reasonable, one survey randomly asked half of all respondents to read the following statement before assessing their level of agreement with commercial peace theory: “Academic studies have consistently found that countries that trade more with each other are less likely to go to war. According to this ‘commercial peace’ theory, trade serves as an important deterrent to military conflict.” Respondents exposed to this “treatment” should be more likely to express support for the commercial peace than respondents who do not read the statement (the control group). However, if security fears trigger instinctive commercial peace responses, as expected, then individuals with high security concerns should not be affected by the treatment, as they will have already internalized the theory; they should, however, have high levels of commercial peace support regardless of treatment.

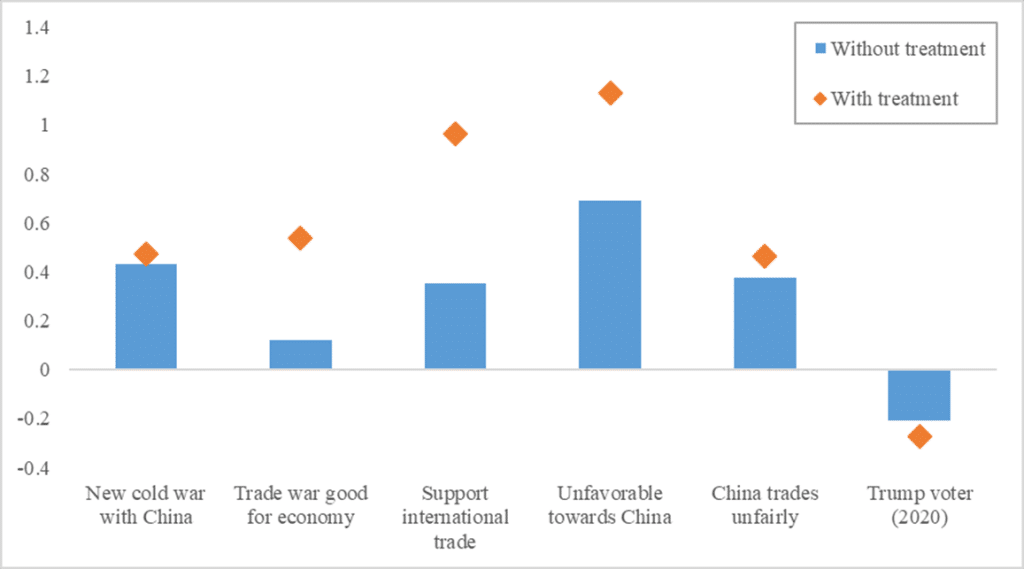

Figure 4 shows how different individual attributes shape responsiveness to the commercial peace treatment. The blue bars represent baseline support for commercial peace theory for the control group, given the independent variable. The orange diamond represents support for commercial peace theory when this population receives the treatment. Overall, as expected, when respondents read about the commercial peace in an experimental setting, they subsequently express greater agreement with commercial peace theory. However, also as expected, this effect disappears for respondents who think that the US and China have entered into a new cold war. Although these respondents have a relatively high baseline belief in commercial peace theory, exposure to the treatment has no significant effect on their belief, implying that individuals with security concerns may have already internalized commercial peace theory. It is also interesting to note that although most individuals respond in expected ways to the commercial peace information cue, Trump voters—who already express low agreement with the commercial peace—are negatively affected by the cue. In other words, hearing about academic support for commercial peace theory makes Trump supporters less likely to agree with the theory, indicating a high degree of skepticism towards academic research.

Note: Each bar/marker combination represents a separate regression with the full set of covariates. Blue bars represent baseline support for commercial peace theory for the control group, given the independent variable, and orange diamonds represent support for commercial peace theory when this population receives the treatment. All copyrights are reserved to the author. For more details, please see the bottom of the page.

Policy Implications

The survey results presented here suggest that Americans with security concerns vis-à-vis China are increasingly opposed to the US-China trade war, and that this phenomenon occurs because individuals have internalized commercial peace theory: many Americans are concerned about war with China and want to end the trade war to make conflict less likely. Given that 55 percent of all respondents identify a new cold war and 68 percent agree with the commercial peace, the findings here have important implications for the American population as a whole. Although traditional trade preference theories help explain initial trade war support, they do not adequately explain changing support for the trade war.

These findings have important policy implications in a context of an increasingly securitized US-China relationship. With increasing antagonism between the United States and China, conventional wisdom holds that political support for further trade decoupling and bilateral protectionist measures will increase. Americans should become increasingly hostile to trade with China, and ending the trade war would be politically unwise. Yet my research findings challenge this narrative. Americans seem to have considerable “liberal”—in the international relations sense—motivations: in the shadow of conflict, they become instinctive commercial peace theorists. Today, as the economic rationale for ending the trade war continues to grow, particularly with stubbornly high inflation, the Biden administration should no longer rely on a faulty political rationale to continue waging the trade war.

Copyright Information: Bulman, D. (2022). Instinctive Commercial Peace Theorists? Interpreting American Views of the US–China Trade War. Business and Politics, 1-33. © The Author(s), 2022. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of V.K. Aggarwal.